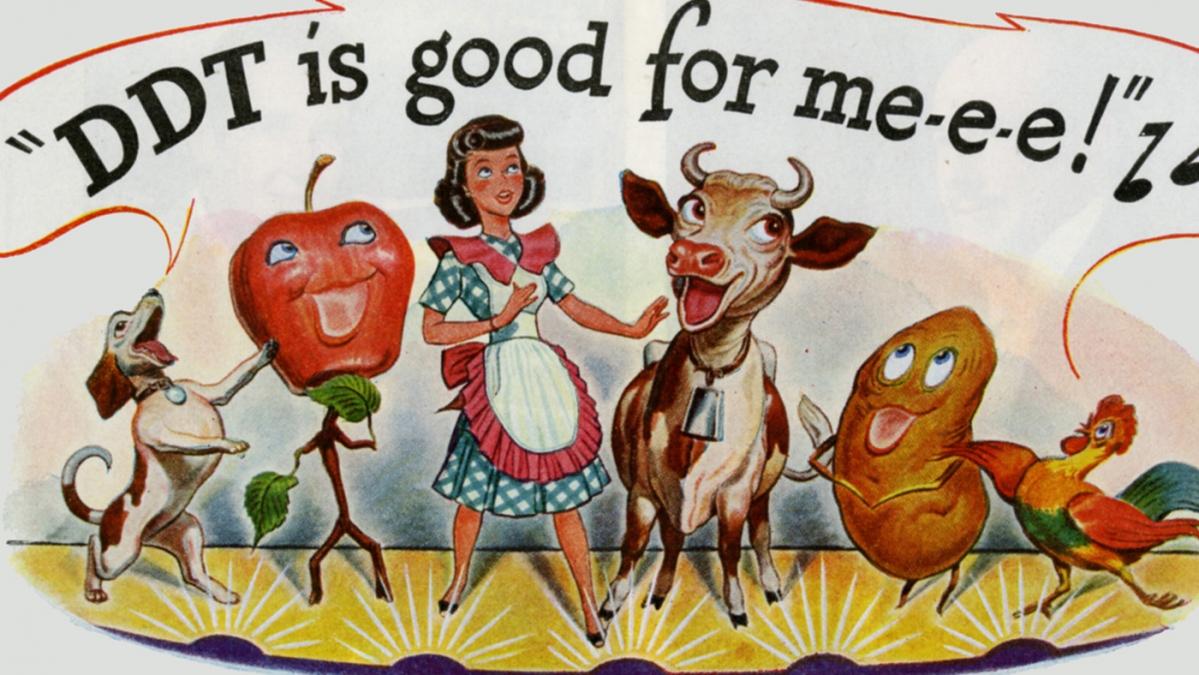

Rachel Carson published the bestselling book Silent Spring in 1962, which alerted the world to the dangers of excessive pesticide use. She called special attention to dichloro-diphenyl-trichloro-ethane (DDT) as one of the most environmentally devastating varieties. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), DDT was highly effective at preventing insect-borne diseases like malaria and typhus while also reducing crop destruction by pests. By 1959, over 80 million pounds of DDT were used annually in the United States. The chemical was favored over others due to the misconception that since its powdered form cannot be absorbed into the skin, it was harmless. However, in most circumstances, DDT is dissolved in oil, rendering it extremely toxic to most organisms.

The impact of Silent Spring ushered in the modern environmental movement and the creation of the EPA in 1970. Much of the book is dedicated to exposing the impacts of DDT on wildlife such as invertebrates, fish, and birds. Carson wrote that nesting bird populations dropped by 90 percent in some towns where DDT spraying was prevalent. In addition to detailing these environmental threats to wildlife, Carson wrote about the human health impacts of DDT. When ingested, the body stores the pesticide in fatty organs like the thyroid, liver, and kidneys.

Due to the bioaccumulation of DDT, ingesting amounts of less than one part per million can result in up to 15 parts per million being stored in the body. When Silent Spring was first released, there was already awareness that DDT was passed between generations. It had been found in breast milk samples, which confirmed that human infants consumed the chemical from birth. Infants are more sensitive to DDT poisoning than adults are, and early exposure can result in negative health impacts that last the rest of a child’s life. Due to public outcries over its adverse effects on wildlife and human health, the EPA eventually banned all DDT use in the US in 1972. More recent studies have confirmed that DDT has serious negative impacts on human health.

DDT has not been used in the United States for nearly 50 years, but researchers have now confirmed that it affects the granddaughters of women who were initially exposed during pregnancy. Scientists at UC Davis and the Public Health Institute of Oakland have tracked blood samples of over 15,000 pregnant women and their children since 1959. Through blood tests and health exams, the initial mothers, daughters, and most recently granddaughters have been monitored. Pregnant mothers were chosen for the initial sample group because DDT is most harmful during periods of high hormonal activity such as pregnancy. The mothers in the study were found to have higher rates of breast cancer, and their daughters had higher breast cancer rates, mammographic density, and obesity levels. The study concluded that the granddaughters also had higher rates of obesity, and began menstruating earlier than average. Both of these indicators are risk factors for breast cancer and heart disease later in life. Because DDT is considered a “forever chemical” that essentially never breaks down, the researchers plan to continue monitoring the health of participants and keep the study going for generations to come.

Despite the well-established knowledge that DDT is harmful to at least three generations beyond the initial exposure, it is still used as an insecticide today. In 2001, a treaty was signed under the United Nations Environment Program that banned 12 toxic persistent organic pollutants, including DDT. The treaty included an exemption that would allow DDT to be used as an insecticide to prevent mosquitoes from transmitting malaria. The World Health Organization expressed support for this stance in 2006, saying that the benefits of malaria prevention outweighed the risks of DDT. These decisions have led to an increase in indoor DDT use over the last 15 years. Over 400,000 people died of malaria in 2019, so environmental health experts largely agree that using DDT is warranted. But, due to the health risks of DDT, using the chemical should be a last resort against malaria, and it should only be used when no other option is present.

Currently, citizens in Ethiopia, South Africa, India, Mauritius, Myanmar, Yemen, Uganda, Mozambique, Swaziland, Zimbabwe, North Korea, Eritrea, Gambia, Namibia, and Zambia use DDT to fight malaria. Although less pesticide is used now than was sprayed across America during the 1960s, there are still serious health concerns. A synthesis study carried out by South African, Dutch, and Swedish researchers found evidence that in regions where DDT is still used, there are elevated levels of various cancers, type two diabetes, hormonal disruption, impaired neurological development, and miscarriages. The researchers suggest that to reduce the harms caused by DDT exposure, safe alternative insecticides should be developed, spraying techniques and equipment should be audited, and chemical handling facilities should be upgraded. To accomplish these goals, more research and funding will be necessary.

The recent approval of a malaria vaccine for children by the WHO may finally offer a viable solution to the DDT paradox. The malaria vaccine is the first ever vaccine approved for use against a parasitic disease, which is a major scientific breakthrough. Over extensive trials, the vaccine has proved to be safe, cost-effective, and it reduced deadly severe malaria by 30 percent. Since the vaccine program is still in its early stages, its true impacts have yet to be seen. However, these advancements are extremely promising, and hopefully DDT will eventually be phased out as malaria is eradicated. The DDT paradox has wreaked havoc for decades, but there is finally hope that it will come to an end.

Sources

Bouwman, H., van den Berg, H., and Kylin, H. (2011, June). DDT and Malaria Prevention: Addressing the Paradox. Environmental Health Perspectives. Retrieved November 19, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3114806/

Carson, R. (1962) Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Cirillo, P.M., La Merrill, M.A., Krigbaum, N.Y., & Cohn, B.A. (2021, August) Grandmaternal Perinatal Serum DDT in Relation to Granddaughter Early Menarche and Adult Obesity: Three Generations in the Child Health and Development Studies Cohort. American Association for Cancer Research. Retrieved November 11, 2021, from https://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/30/8/1480

Cone, M. (2009, May 4) Should DDT Be Used to Combat Malaria? Scientific American. Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ddt-use-to-combat-malaria/

EPA. (2021, November 4) DDT – A Brief History and Status. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/ddt-brief-history-and-status

Nichols, J. (2020, March 18) DDT’s toxic legacy could span three generations. Grist. Retrieved November 11, 2021, from https://grist.org/justice/ddts-toxic-legacy-could-span-three-generations/

WHO. (2020) World malaria report 2020. World Health Organization. Retrieved November 19, 2021, from https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2020

Xia, R. (2021, April 14) DDT’s toxic legacy can harm granddaughters of women exposed, study shows. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 11, 2021, from https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2021-04-14/toxic-legacy-of-ddt-can-harm-granddaughters-of-women-exposed