Within the pristine rivers and tributaries of southwest Alaska from June to late July, it is impossible to miss the crimson sockeye salmon as they travel upstream to spawn the next generation of anadromous fish. Alaska’s Bristol Bay is home to the natal spawning streams for all five species of Pacific salmon: sockeye, coho, Chinook, chum, and pink. These cold freshwaters are a familiar sight for the adult salmon who will return here to breed after spending two to five years maturing at sea.

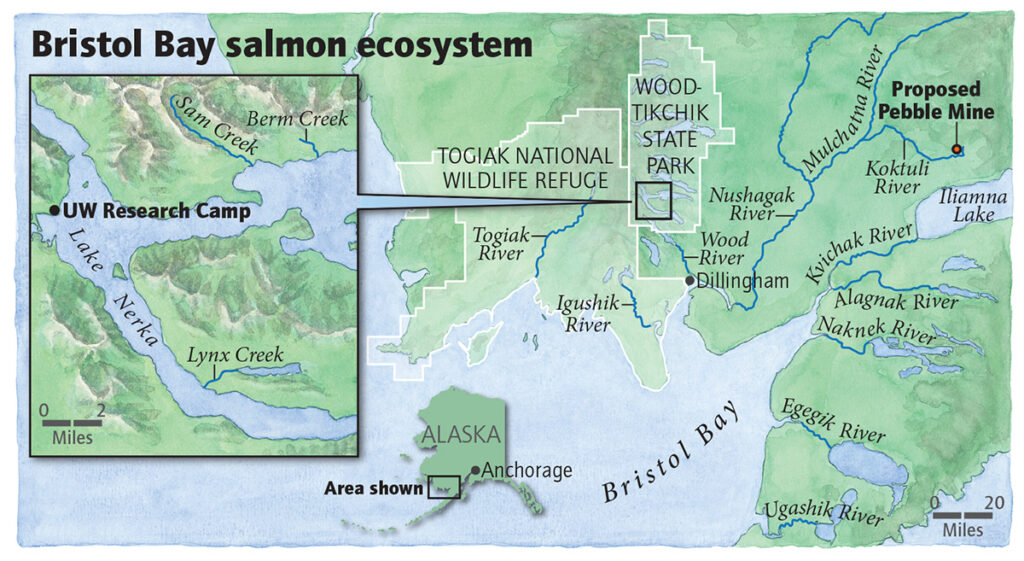

Bristol Bay is situated between the Alaskan Peninsula and Cape Newenham before emptying into the Bering Sea. Bristol Bay is one of North America’s most productive marine ecosystems, supporting rich biodiversity, fisheries, and recreational activities. Bristol Bay’s watershed is composed of six major river basins. The two largest, Nushagak and Kuichak, contribute to nearly half its total watershed. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), “The Bristol Bay watershed provides vital habitat for 29 fish species, more than 190 bird species, and more than 40 terrestrial mammals.” Bristol Bay supports the most abundant sockeye salmon migration in the world and is a refuge for wildlife amidst the constant threat of a warming subarctic region.

In late summer, thousands of vibrant red fish repopulate rivers throughout the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia, Canada. This is a beacon for fishermen and coastal communities, for which the salmon provide a source of food and income. This spectacular display of life attracts biologists, filmmakers, and fishing enthusiasts to the region in pursuit of curiosity or inspiration. The annual return of salmon functions as Mother Nature’s calendar, around which so many lives and livelihoods in the region revolve. However, in recent years this annual migration has become more uncertain. Disturbances in the timing of the migration are causing communities to reimagine their dependence on salmon populations. The shifting salmon migrations affect both the ecological community structure and the human communities that depend on them.

The salmon’s life cycle begins in the freshwater streams of Bristol Bay. After three years, they will reach the smolt stage and migrate to the ocean to grow and feed on zooplankton, where they will spend two to three years maturing at sea before they return to the same freshwater location where they were born. Adult salmon then spawn in these streams before they die within a few weeks. Thus, the salmon’s life cycle begins again in an intricate display of nature’s resilience. Even the salmon’s carcass plays a role in the river ecosystem as it releases nitrogen and phosphorus compounds into the water. Salmon carcasses provide a source of energy and nutrients found to improve the growth of newly hatched salmon.

Salmon are among the few anadromous creatures on earth, or those that migrate from the sea to rivers to spawn. However, warming global temperatures are affecting the migration of juvenile sockeye salmon as they journey from their natal freshwater habitats to the Pacific Ocean. As freshwater streams become warmer, salmon are more susceptible to disease, which may lead to disruptions in their breeding efforts. One concern is that as water temperatures increase, the salmon’s developmental rate may be disturbed. Warmer waters may cause juvenile salmon to develop more rapidly and migrate to the Pacific Ocean before their planktonic food source has reached sufficiently high levels. The timing of these planktonic ‘blooms’ is influenced by climatic factors, potentially limiting the salmon’s food source. Climate change also causes temporal shifts of freshwater inputs that further contribute to the loss of habitats suitable for spawning.

As air temperatures warm, snow that feeds into the freshwater system is expected to melt earlier in the season and be replaced by rain. Reduced summer flows increase water temperatures even more, while increased winter flows lead to erosion and the disturbance of juvenile salmon. This limits the habitats suitable for salmon to spawn. However, not all salmon populations will be affected by climate change in the same way. Some sockeye populations in Alaska have been observed to benefit from the availability of new spawning habitats created by warming temperatures. Yet, climate change is not the only threat to salmon; humans are significantly changing the environments salmon depend on through other destructive activities.

The most urgent concern is the proposed Pebble Mine project, which would “destroy 3,000 acres of wetlands and 21 miles of salmon streams.” This gold and copper mine deposit would be located at the headwaters of the Bristol Bay watershed, beneath the two most productive rivers in a seismically active region. According to the World Wildlife Fund, “the scar on Alaska’s pristine, productive environment would be visible from space.” Environmentalists, anglers, and Native Alaskan communities have strongly opposed this mining project for over a decade. In May of this year, President Biden announced a legal ban on metal waste disposal in the Bristol Bay watershed, citing the Clean Water Act of 1972. If finalized, the ban would signify the end to a long and controversial effort by the mining industry to extract metals in Bristol Bay and allow the EPA to have legal protection over the world’s most valuable sockeye salmon fishery. This is a major victory for tribes, environmentalists, fishermen, and coastal communities who recognize that the health of the ecosystem is essential to their communities.

The lifestyles of Indigenous communities, like so many in the remote region of Bristol Bay, depend on the health of the salmon. The indigenous peoples within and around Bristol Bay have long cultivated a relationship with the land and surrounding waters. In Yup’ik, they call it Yuuyaraq, the way of life. According to the EPA, “Salmon are integral to the entire way of life in these cultures as subsistence food and as the foundation for their language, spirituality, and social structure.” Bristol Bay itself is home to twenty-five Alaskan Native communities, fourteen of which reside along the Nushagak and Kuichak rivers. Indigenous cultures within the Bristol Bay watershed include the Yup’ik and Dena’ina, communities that depend on fish and moose for 80% of their protein. These indigenous communities are “two of the last intact, sustainable salmon-based cultures in the world.” However, the stories of the indigenous people who are so intricately connected with the life cycles of salmon are largely unrepresented, which contributes to a loss of scientific understanding and public awareness. The continuation of their subsistence-based lifestyles depends on intergenerational knowledge exchange and the preservation of cultural value systems passed down through generations.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently lists sockeye salmon at a level of least concern, as the global distribution is relatively stable. However, there are subpopulations throughout the Pacific Northwest that are considered “near threatened” or “endangered.” Salmon were once much more abundant. However, one hundred years ago, overfishing became a major threat to salmon populations and by the late 20th century, salmon populations had drastically declined. Today, the largest sockeye salmon fishery in the world is located in Alaska’s Bristol Bay, with approximately 46% of the global sockeye salmon population originating there. According to the World Wildlife Fund, Alaska’s wild salmon fishery is “valued at more than $1.5 billion and provides nearly 20,000 jobs throughout the United States annually.”

Human societies depend on salmon populations. The iconic red fish is more than a source of food and income, it connects communities in this remote region of Alaska through a shared way of life. As climate change continues to warm this region at a rapid rate, societies may be forced to adapt in ways that allow future generations to thrive. No matter what the future holds for southwest Alaska, the people and ecosystems of Bristol Bay are woven together through a shared dependence on wild sockeye salmon.

Sources

“About Bristol Bay.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 8 September 2022, https://www.epa.gov/bristolbay/about-bristol-bay. Accessed October 30, 2022

Davenport, Coral. “Biden Administration, Settling a Long Feud, Moves to Block a Mine in Alaska.” New York Times, 25 May 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/25/climate/pebble-mine-alaska-epa.html. Accessed October 30, 2022.

Fisheries, NOAA. “Sockeye Salmon.” NOAA, 2019. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/sockeye-salmon.

“Salmon and Climate Change .” IUCN Red List, 2009. https://www.weadapt.org/sites/weadapt.org/files/legacy-new/placemarks/files/533ac6c85a5e0fact -sheet-red-list-salmon.pdf.

“Salmon of the West – Why Are Salmon in Trouble?” U.S Fish & Wildlife Service. Accessed October 30, 2022. https://www.fws.gov/salmonofthewest/trouble.htm.

“Sockeye Salmon.” National Geographic, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/facts/sockeye-salmon.

“Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus Nerka).” Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Accessed October 30, 2022. https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=sockeyesalmon.printerfriendly.

“Sockeye Salmon and Climate Change.” WWF. World Wildlife Fund. Accessed October 30, 2022. https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/sockeye-salmon-and-climate-change.

Stark, Devon. “A Brief History of Salmon Fishing in the Pacific Northwest.” Mid Sound Fisheries Enhancement Group. Accessed October 30, 2022. https://www.midsoundfisheries.org/a-brief-history-of-salmon-fishing-in-the-pacific-northwest/.

“Why Is Bristol Bay Important for Salmon? and Seven Other Bristol Bay Facts.” WWF, World Wildlife Fund, https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/why-is-bristol-bay-important-for-salmon-and-seven-other bristol-bay-facts.