On August 7, 2008, the Massachusetts legislature ratified the Global Warming Solutions Act (GWSA) with the intention of cutting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions state-wide. Massachusetts’ Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EOEEA), in collaboration with other state agencies and the public, set out to devise GHG emission reduction goals to help Massachusetts reduce its carbon footprint. The initial goals were straightforward: reduce statewide GHG emissions by 10-25% from 1990 emissions levels by 2020, and reduce emissions by 80% from 1990 levels by 2050. With 2020 coming to an end, now is a good time to examine the GWSA’s implementation progress.

Upon its ratification, the GWSA proposed a set of deadlines to help guide the act’s completion. By January 1 of 2009, the GWSA required reporting regulations for the state’s largest GHG emitters so that the EOEEA could determine the precise emissions of these companies and utilities. These emissions records, in tandem with the 1990 GHG emissions levels, would create a benchmark to gauge the act’s progress in the years to come. Additionally, by January 1 of 2011, the EOEEA and its collaborators had to come up with an achievable goal for GHG emissions reductions by 2020 assuming “business as usual” conditions (or, in other words, in a scenario where no further programs are launched specifically targeting emission reduction). This goal would have to incorporate concrete methods to achieve the set goals for 2020. Finally, by the end of December 2009, the GWSA required the team, through the assistance of an advisory committee, to submit a list of strategies to plan for future climate change adaptation. However, the GWSA did not roll out as smoothly as environmentalists had hoped.

Before the Massachusetts legislature passed the act, the GWSA was opposed by those who claimed it would cost jobs and detract from economic growth. The act was not terribly successful in the first few years following its ratification in 2008, due to neglect from an ambivalent government. Massachusetts witnessed rising GHG emission levels from 2009-10 and from 2013-14. The GWSA’s progress was slow, and at times seemed to reverse, but the implementation committee kept pushing with some help from environmental organizations like the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) and from public activism.

David Ismay, a senior attorney for the CLF, argued that by January 1, 2012, the GWSA had yet to promulgate any of the regulations that would help achieve the 2020 GHG emissions goal. The GWSA had assigned the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) the task of promoting regulations necessary to achieve the act’s 2020 goal. Ismay insisted, however, that MassDEP failed to carry out this order, and subsequently, CLF went to court in 2014, seeking to hold the MA legislature accountable.

Ismay and the CLF emerged from their lawsuit victorious. Although they were fought by the administrations of Massachusetts Governors Deval Patrick and Charlie Baker, the CLF persevered due to a declared lack of necessity for these regulations. The Massachusetts Supreme Court settled the lawsuit, generating a sense of reinstilled hope among proponents of the act.

In the years following the 2014 lawsuit, Massachusetts saw a further decline in GHG emissions. The GWSA hit its stride and issued yearly reductions in GHG emission caps per GHG-producing facility. In 2016, Governor Baker even issued an executive order to establish new GHG emission goals for 2030 and 2040, in which the state would work with transportation services and advisory committees to craft new methods of reducing MA’s carbon footprint.

However, in 2017, the GWSA’s progress was again threatened. The New England Power Generators Association filed a complaint in 2017 against MassDEP in regards to the GHG emissions limitations on electricity generators. The trade association and power plant owner that filed the complaint maintained that the emissions regulations were too severe, and therefore unjust. The owner moved for judgment on the complaint hearings in mid-January, 2018, and by the end of the month, the case had moved to County Court. The case quickly transitioned to the Supreme Judicial Court, where the trade association and power plant owner argued that the year-to-year declining GHG emissions restrictions went beyond the authority of the GWSA. Following a series of filed briefs, though, including an amicus brief (a brief filed by an impartial advisor) from the CLF calling for the preservation and continued adherence to the regulations, the lawsuit finally concluded in September of 2018 by allowing the GWSA to continue regulating GHG emissions as it had been prior to the complaint.

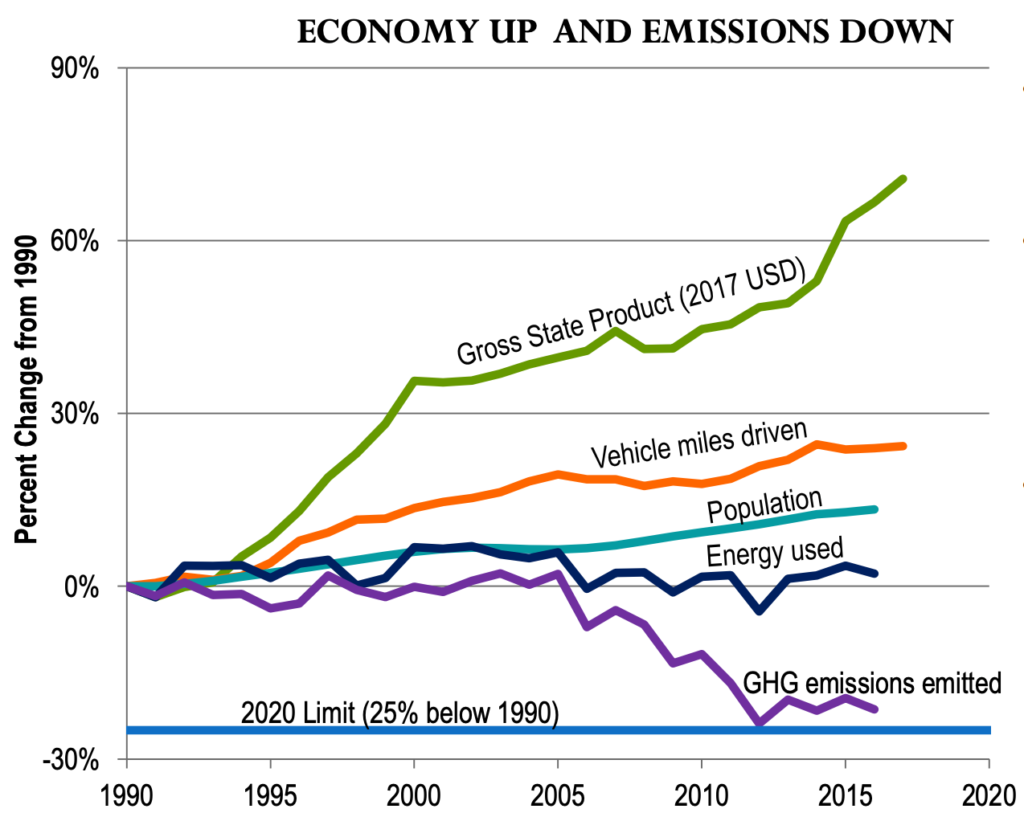

As a result of public support for the GWSA and the efforts of the CLF, Massachusetts has kept on target with its 2020 emission goal. Although the final emissions totals in 2020 have yet to be determined, the EOEEA’s GWSA 10 Year Progress Report highlights a negative trend in emissions, as shown in the following graph:

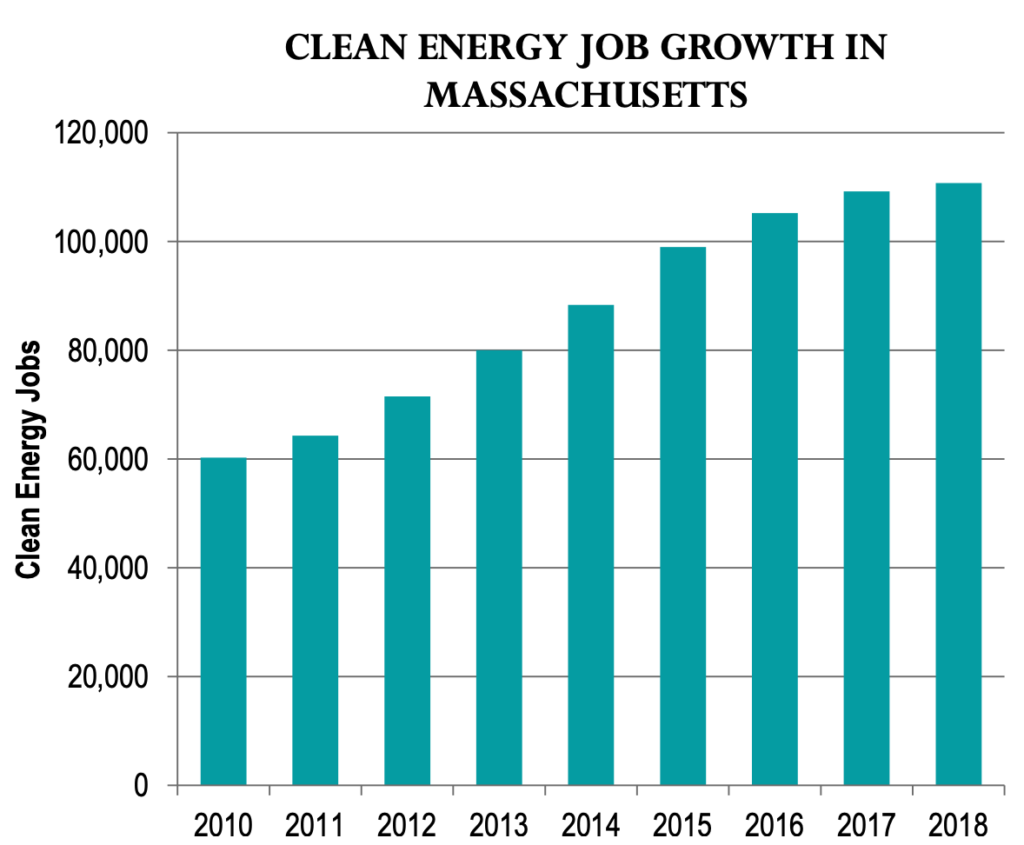

In contrast to the claims of initial GWSA opponents that the act would cost jobs, the 10 Year Summary also depicts substantial job growth in the clean energy sector.

With 2020 wrapping up, the first major goal of the GWSA has yet to be achieved, but the prospects are high. Sustained support from an ever-increasing list of environmental organizations, along with activism across the state, can help improve Massachusetts’ carbon footprint, and therefore can help in the fight against climate change.

Sources

Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. (2019, January 23). Global Warming Solutions Act 10 Year Progress Report. http://ma-eeac.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/EEAC-Jan-23-GWSA-10-Year-Progress-Report.pdf

Executive Order No. 569: Establishing an Integrated Climate Change Strategy for the Commonwealth | Mass.gov. (n.d.). Mass.Gov. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.mass.gov/executive-orders/no-569-establishing-an-integrated-climate-change-strategy-for-the-commonwealth

Global Warming Solutions Act Background. (n.d.). Mass.Gov. Retrieved October 11, 2020, from https://www.mass.gov/service-details/global-warming-solutions-act-background

Global Warming Solutions Acts. (n.d.). Conservation Law Foundation. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.clf.org/making-an-impact/global-warming-solutions-act/

GWSA Implementation Progress. (n.d.). Mass.Gov. Retrieved October 11, 2020, from https://www.mass.gov/service-details/gwsa-implementation-progress

Kain v. Department of Environmental Protection. (2014). Climate Change Litigation Databases. http://climatecasechart.com/case/kain-v-department-of-environmental-protection/

MassDEP Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reporting Program. (n.d.). Mass.Gov. Retrieved October 11, 2020, from https://www.mass.gov/guides/massdep-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reporting-program

New England Power Generators Association v. Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection. (2017). Climate Change Litigation Databases. http://climatecasechart.com/case/new-england-power-generators-association-v-massachusetts-department-environmental-protection/

Reilly, A. (2017, July 13). Law and Effect: The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2008. WGBH. https://www.wgbh.org/news/2017/07/13/politics-government/law-and-effect-global-warming-solutions-act-2008

Session Law—Acts of 2008 Chapter 298. (2008, August 7). The 191st General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. https://malegislature.gov/Laws/SessionLaws/Acts/2008/Chapter298