Just off the coast of Belize lies the second-largest barrier reef in the world. Home to an abundance of biodiversity, the Belize Barrier Reef hosts nearly 1,400 different species. Of those organisms, lionfish were only recently introduced to the ecosystem. Native to the Indian and Pacific Oceans, Pterois volitans and Pterois miles, two species of lionfish, were first sighted off the coast of Florida in 1985. Since then, they have spread rapidly up the east coast of the United States, to the Gulf of Mexico, and throughout the Caribbean Sea.

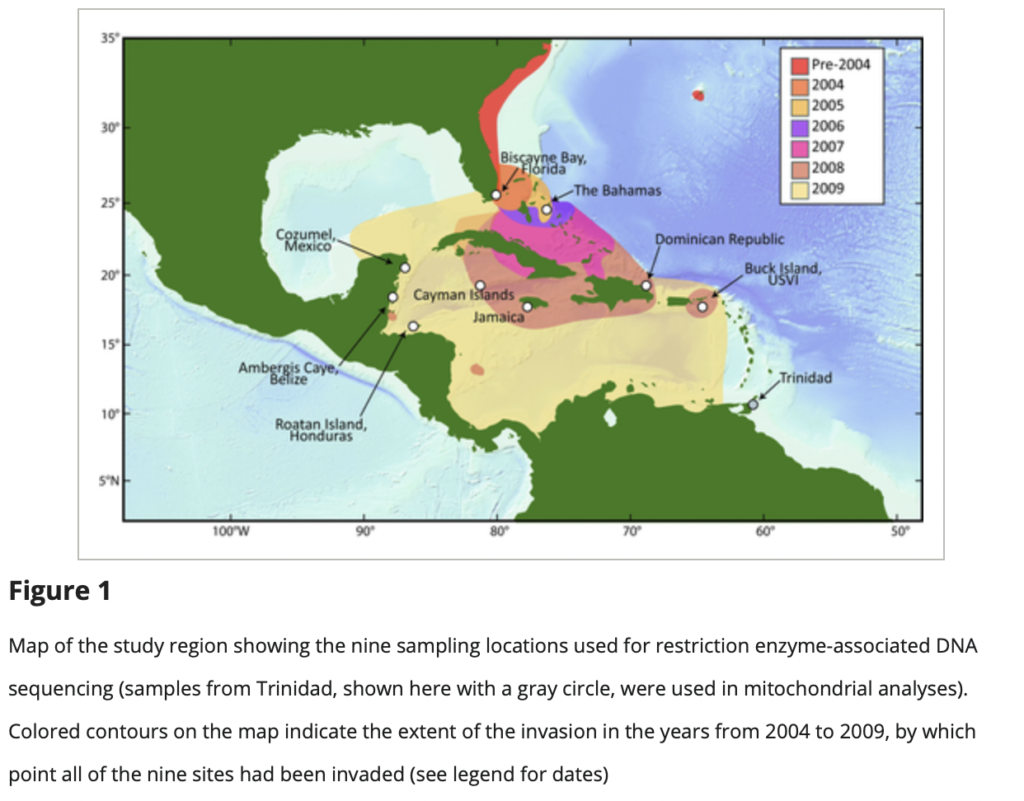

The reason lionfish were released in this area is largely unknown, but scientific organizations like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) predict they were introduced to the Atlantic Ocean through “the aquarium trade.” One possible explanation is that, in 1992, Hurricane Andrew destroyed a private aquarium in Florida, releasing lionfish into the ocean. Although lionfish were seen off the coast of Florida years before, it was not until the 2000s that they began to spread beyond the initial location. The figure below shows the years in which lionfish spread to different regions.

The threat of long-term impacts brought on by the lionfish invasion was described by Mark A. Albins and Mark A. Hixon as “the worst-case scenario.” Biological invasions contribute to biodiversity loss, significant ecosystem destruction, and immense environmental and economic costs. The spread of lionfish has and will continue to cause detrimental damage to marine ecosystems.

There are many factors that make lionfish successful invaders and give them a competitive advantage against native species. Lionfish reach sexual maturity after just one year and they have the ability to produce 30,000 to 50,000 eggs every three days. This allows them to quickly outnumber native organisms. Lionfish are known to be “indiscriminate eaters,” meaning they will eat anything they can fit in their mouths. In their native range, lionfish predators include sharks, eels, groupers, and snappers. However, they have no “natural predators in their invasive range,” and other potential predators are overfished which has facilitated the population boom. According to the Belize Lionfish Project, “scientists are concerned that [Belize’s] already stressed fisheries and coral reef ecosystems will become even more taxed if lionfish are not kept in control.”

The rapid increase of lionfish in the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean not only contributes to a decrease in the population of native organisms; there is also an indirect effect on coral reef systems. Lionfish feed on parrotfish, which are now facing population depletion. As parrotfish are herbivores and typically consume seaweeds, they allow “reef-building” corals to grow without competition. Lionfish “reduce the abundance of herbivores, thereby indirectly negatively affecting reef corals by fostering seaweed growth.” These two factors together—the increase of invasive lionfish and the increase of native seaweed—create a negative impact on these reef-building corals.

As a detriment to ecosystems with no natural predators, communities have sought to reduce the lionfish population by hunting them. Many coastal communities have shifted towards tourism as opposed to the fishing industry, so allowing tourists to hunt for lionfish while exploring the Belize Barrier Reef has become increasingly popular. Ecotourism accounts for about 30% of Belize’s GDP, so hunting for lionfish creates a positive impact on both Belize’s economy and its coral reefs. A report by A. Diedrich found that:

“Because the observed relationship may be dependent on continued benefits from tourism as opposed to a perceived crisis in coral reef health, Belize must pay close attention to tourism impacts in the future. Failure to do this could result in a destructive feedback loop that would contribute to the degradation of the reef and, ultimately, Belize’s diminished competitiveness in the ecotourism market.”

The obvious solution to the lionfish invasion is to get rid of lionfish; however, according to the NOAA, “removing lionfish from the southeast United States continental shelf ecosystem would be expensive and likely impossible.” Instead of spending thousands of dollars to dive and hunt for lionfish as a tourist, another effective practice is supporting businesses that use lionfish in their products. Whether it is eating lionfish at restaurants or buying jewelry made of lionfish skin, it is important to support companies that promote sustainability alongside the mitigation of invasive species. INVERSA Leathers co. makes accessories out of invasive species leather, and was established because the co-founders “witnessed firsthand the devastation caused by invasive lionfish to the coral reefs.” INVERSA focuses on “human-introduced, severe impact species,” meaning they deal with invaders that were transported by humans. Sarah Zelinski, a writer for Smithsonian Magazine, reminds readers that invasive organisms are not to blame for destruction, humans are — and it is up to us to safely remove them before they cause irreversible damage. Companies like INVERSA go above and beyond in this effort by creating jobs and generating revenue to drive invasive species management and removal.

An article by Samhouri and Stier argues that “the effects of invasive species are not uniformly negative.” While some invasive species can have a positive impact on a country’s socioeconomic opportunities, in comparison to other native mesopredators, Mark Albins found that lionfish living in Bahamian coral reef ecosystems had a much larger negative impact. They specifically harmed species richness and reduced the abundance of small, native fish in the reef community. In contrast, Samhouri and Stier’s study shows that lionfish in Caribbean Panama show “indistinguishable” effects on native prey from native mesopredators. These results support the view that “management of invasive lionfish may be succeeding in some places and that continuation of control efforts requires nuanced consideration in relation to specific conservation goals and in relation to other environmental concerns.” There is much work to be done, but it is encouraging to know the increased efforts are working, even if it is on a small scale.

Perhaps this “worst case scenario” may not reach its full potential. A growing number of lionfish in The Gulf of Mexico have been showing signs of ulcerative skin disease. This could be a result of “high densities and low genetic diversity.” A study conducted by Harris et al. found evidence that “density-dependent epizootic population control” may help mitigate lionfish populations and help scientists further understand invasive species invasions.

Lionfish, like many invasive species, are threatening marine biodiversity by directly and indirectly changing marine ecosystems. Each event has created the perfect storm which allows lionfish to invade and harm native species. Not only does this impact marine organisms, but also the people whose livelihoods depend on them. Research shows that one lionfish can reduce native reef fish recruitment by 79%, directly affecting commercial and recreational fisheries. These threats are irreversible, but reducing the number of invasive lionfish will allow affected communities to somewhat recover. To help these efforts, support sustainable companies that work to eliminate invasive species, learn more about invasive species around the world, and be conscious of how small choices can have a great impact.

Sources

Albins, Mark A. “Effects of Invasive Pacific Red Lionfish Pterois Volitans versus a Native Predator on Bahamian Coral-Reef Fish Communities – Biological Invasions.” SpringerLink, Springer Netherlands, 23 June 2012, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10530-012-0266-1.

Albins, Mark A., and Mark A. Hixon. “Worst Case Scenario: Potential Long-Term Effects of Invasive Predatory Lionfish (Pterois Volitans) on Atlantic and Caribbean Coral-Reef Communities – Environmental Biology of Fishes.” SpringerLink, Springer Netherlands, 15 Apr. 2011, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10641-011-9795-1. Belize Lionfish Project, https://www.belizelionfish.org/history.html.

“Belize’s Incredible Barrier Reef Is Removed from UNESCO’s List of World Heritage in Danger.” WWF, World Wildlife Fund, 26 June 2018, from https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/belize-s-incredible-barrier-reef-is-removed-from-u nesco-s-list-of-world-heritage-in-danger#:~:text=Comprised%20of%20seven%20protecte d%20areas,six%20threatened%20species%20of%20sharks.

Bors , Eleanor K, et al. Population Genomics of Rapidly Invading Lionfish in the Caribbean … 10 Jan. 2019, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ece3.4952.

FAQ, from https://www.inversaleathers.com/faq.

Fisheries, NOAA. “Impacts of Invasive Lionfish.” NOAA, from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/southeast/ecosystems/impacts-invasive-lionfish#:~:text= Researchers%20have%20discovered%20that%20a,other%20commercially%20important %20native%20species.

Hare, Jonathan A., and Paula E. Whitfield. An Integrated Assessment of the Introduction of Lionfish (Pterois … Dec. 2003), from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277192703_An_Integrated_Assessment_of_the _Introduction_of_Lionfish_Pterois_volitansmiles_complex_to_the_Western_Atlantic_Oc ean.

Harris, Holden E., et al. “Precipitous Declines in Northern Gulf of Mexico Invasive Lionfish Populations Following the Emergence of an Ulcerative Skin Disease.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 4 Feb. 2020, from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-58886-8.

“Invasive Lionfish.” Invasive Lionfish | Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, from https://flowergarden.noaa.gov/education/invasivelionfish.html#:~:text=Lionfish%20aren’t %20recognized%20as,to%20keep%20from%20being%20eaten.

“Invasive Lionfish.” Invasive Lionfish | Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, from https://flowergarden.noaa.gov/education/invasivelionfish.html.

Samhouri, Jameal F., and Adrian C. Stier. “Ecological Impacts of an Invasive Mesopredator Do Not Differ from Those of a Native Mesopredator: Lionfish in Caribbean Panama – Coral Reefs.” SpringerLink, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 4 July 2021, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00338-021-02132-8.

Zielinski, Sarah. “Are Humans an Invasive Species?” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 31 Jan. 2011, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/are-humans-an-invasive-species-42999 965/.