The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced their proposal on August 26, 2022 to add two commonly-used per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to the list of hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA).

The proposed designation was first announced during its preliminary stage in late 2020. With the Biden-Harris Administration’s transition into the White House, the team placed greater focus on environmental justice and safety. In late 2021, EPA Administrator Michael Regan and his team launched the “PFAS Strategic Roadmap: EPA’s Commitments to Action 2021-2024,” often shortened to the ‘Roadmap.’ The Roadmap details an EPA-wide commitment to protecting public and environmental health from PFAS. The proposal to designate two widely-used PFAS as hazardous substances is one of the foundational promises of the PFAS Roadmap and the first step on a long road of environmental and PFAS-related protections. Though the EPA published the proposal in late August of 2022, they will continue to accept public comments and recommendations on the designation through 2023, at which point the EPA will finalize the proposal into law.

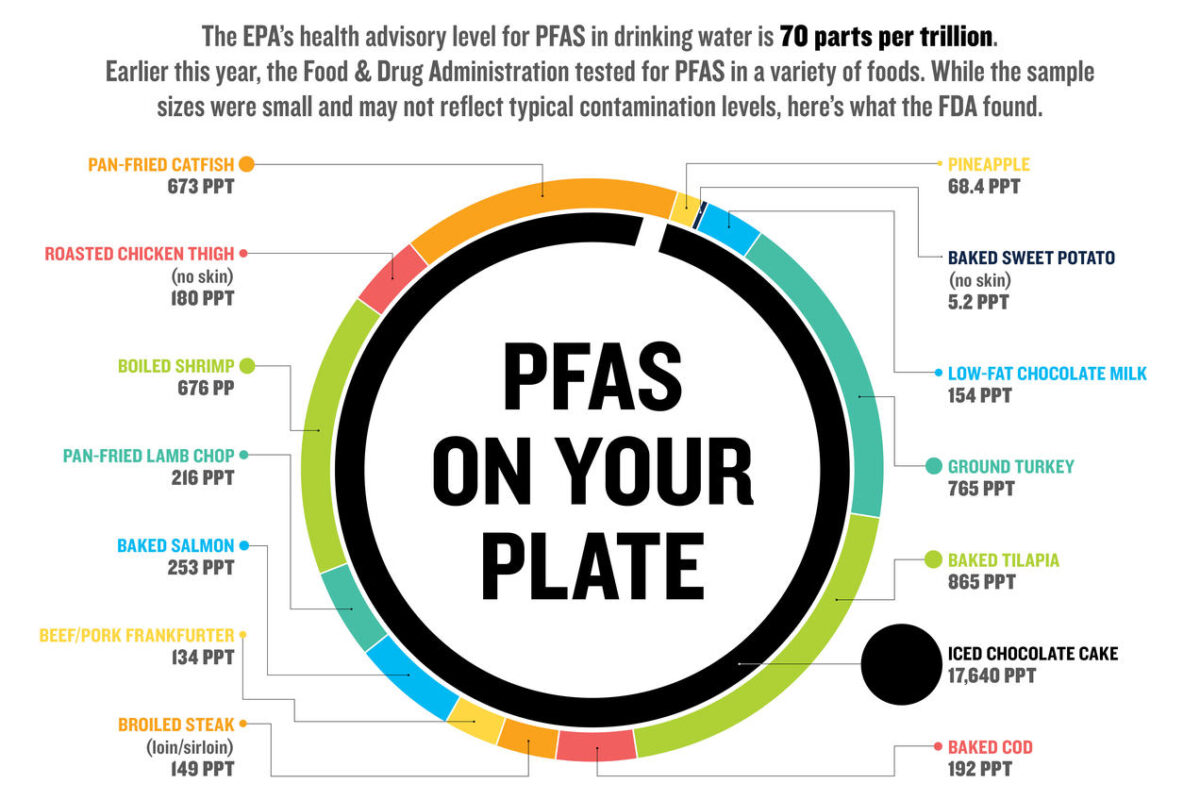

Over 12,000 anthropogenic chemicals make up the class of PFAS. These chemicals are often referred to as “forever chemicals” due to their resistance to heat, water, and oil. Their stability and resilience against contact with other chemicals allow manufacturers of products like clothing, non-stick cookware, ski wax, and fire extinguisher foam to utilize PFAS for surface and protective coatings. Despite these now commonplace uses, the chemicals pose a significant health hazard, as their stability and long-lasting nature mean they can remain in the environment—and even human bodies—for years. In regions with significant water pollution, such as those near industrial plants, studies have found higher human blood concentrations of PFAS.

CERCLA, also known as Superfund, acts as the federal fund for cleaning up uncontrolled or abandoned hazardous waste dump sites, spills, and other releases of designated pollutants. CERCLA gives the EPA the power to contact the responsible party (or parties) to ensure their cooperation in the cleanup. The Superfund, specifically Section 102, allows the EPA Administrator to classify additional substances as hazardous when they present environmental and public health risks. By labeling certain PFAS as hazardous substances, the EPA increases transparency surrounding chemical releases and the accountability of polluters for cleaning up said releases.

The EPA proposes adding two specific PFAS to CERCLA’s list of hazardous substances: perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). In 2016, the EPA initiated a phase-out of the production and use of both chemicals in American-made goods, leading to an eventual ban. The legislation did not, however, require imported goods to comply with the new standards; thus, PFOA and PFOS still enter the American market and impact American residents. Studies continue to conclude that most PFAS are harmful to human and environmental health even at low levels, and substantial evidence supports the theory that PFOA and PFOS can cause cancer, reproductive and developmental issues, and cardiovascular, liver, and immunological complications. EPA Administrator Regan cited these health risks as his reasoning behind designating the two PFAS as hazardous substances.

Those in favor of environmental protections and regulations see this proposal as a major step in the right direction. Corporations and other polluters, however, consider the labeling of two major PFAS as hazardous substances to be harmful to their operations. In particular, closed and nearly closed CERCLA sites, in which the cleanup of hazardous substances was or will soon be completed, could be reopened or have the cleanup timeline pushed back if scientists detect PFOA and/or PFOS on the site. Any site with PFOA and/or PFOS present will fall under CERCLA, as the purpose of this designation is to remove all presence of the chemicals, not just new releases. Additional CERCLA sites could be opened as well if either chemical is present. The proposed designation also opens up CERCLA requirements to numerous potentially responsible parties that had not previously been considered. Farmers who used to spray their crops with PFA-containing pesticides could have their property labeled a Superfund site in need of hazardous substance cleanup. Importantly, the EPA’s proposed hazardous substance designation of PFOA and PFOS paves the way for the EPA to take further steps by placing other harmful PFAS under CERCLA’s jurisdiction.

Researchers recently found a way to degrade PFAS, providing a light at the end of the tunnel for those facing the negative effects of PFAS contamination. PFAS naturally have extremely high resistance to most common methods used to break down chemicals. While their makeup provides numerous attractive uses in consumer products, the same properties allow PFAS to resist degradation in the environment for long periods of time. In the human body, PFAS can last up to 8 years, accumulating every day. However, recent studies have shown PFOA and PFOS do not degrade naturally in the environment without anthropogenic intervention. For example, plasma-based degradation methods have proven useful, though harsh, in breaking down various classes of PFAS. This process uses electricity to convert water into many extremely reactive substances, also called plasma. After this, the system pumps in argon gas to create a foam layer at the top of the liquid; this foam layer concentrates substances like PFAS and exposes them to the reactive and degradative species in the plasma, which then breaks apart those PFAS. This method has specifically proven successful in breaking down PFOA and PFOS as well.

While these new methods prove promising, implementation has not been wide enough to protect the population at large. The good news is that there are some steps people can take to reduce their vulnerability. People obtaining their drinking water from public water systems can utilize a filtration system to reduce PFAS exposure. Ingesting fish caught in waterways known to have been contaminated by PFAS can induce health hazards; therefore, people should ensure their fish did not originate in polluted waters.

Labeling two commonly-used PFAS as hazardous sets a promising precedent for possible future labeling of other harmful PFAS to protect public health in the US. The proposal will be put into law sometime in 2023; until then, if anyone would like to submit comments, follow this link! To learn even more, check out EcoWatch’s complete PFAS guide.

Sources

California State Water Resources Control Board. (2022, October 4). PFAS: Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. California Water Boards. Retrieved from https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/drinking_water/certlic/drinkingwater/pfas.html

EPA Proposes Designating Certain PFAS Chemicals as Hazardous Substances Under Superfund to Protect People’s Health. (2022, August 26). US EPA. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-proposes-designating-certain-pfas-chemicals-hazardous-substances-under-superfund

Johnson, T. (2018, August 2). Breaking down the Forever Chemicals – What are PFAS? Clean Water Action Minnesota. Retrieved from https://www.cleanwateraction.org/2018/08/02/breaking-down-forever-chemicals-–what-are-pfas

Meaningful and Achievable Steps You Can Take to Reduce Your Risk. US EPA. (2022, August 18). Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/pfas/meaningful-and-achievable-steps-you-can-take-reduce-your-risk

Overview presentation: NPRM designation of PFOA and PFOS as CERCLA … US EPA. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-09/Overview%20Presentation_NPRM%20Designation%20of%20PFOA%20and%20PFOS%20as%20CERCLA%20Hazardous%20Substances.pdf

Perfluorooctanic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), and Related Chemicals. American Cancer Society. (2022, July 28). Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/healthy/cancer-causes/chemicals/teflon-and-perfluorooctanoic-acid-pfoa.html

Pujari, D., Rheinheimer, C. A., & Leifer, S. (2022, September 26). Potential Impacts of the EPA’s Designation of PFAS as Hazardous Substances. WilmerHale. Retrieved from https://www.wilmerhale.com/insights/client-alerts/20220926-potential-impacts-of-the-epas-designation-of-pfas-as-hazardous-substances

Singh, R. K., Fernando, S., Baygi, S. F., Multari, N., Thagard, S. M., & Holsen, T. M. (2019). Breakdown Products from Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances (PFAS) Degradation in a Plasma-Based Water Treatment Process. Environmental Science & Technology, 53, 2731-2738. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b07031

Summary of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (Superfund). US EPA. (2022, September 12). Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-comprehensive-environmental-response-compensation-and-liability-act